The treatment of sleep disorders is an area that is expanding in medical care and physicians are currently placing more importance on sleep as a primary or secondary risk factor for many systemic conditions. In addition, dentists have been participating in the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders, and this article aims to review the basic concepts of sleep disorders and the dentist’s role in the care of affected patients.

Its role in Dentistry

Every dentist who evaluates and treats patients with hypertension, bruxism, chronic fatigue, headaches or jaw pain of muscular origin has observed that the patient may have a sleep problem that contributes to the primary diagnosis. The role and involvement of dentistry in the diagnosis and treatment plan of a patient with sleep disorders can be direct or indirect.

The indirect approach

This method mainly consists in recognising what is suspected to be a sleep disorder problem, educating the patient and appropriately referring them to treatment. This referral may be to the primary care physician or to a physician specialising in sleep medicine. Examples of sleep disorders that can be recognised by a dentist include1:

- Insomnia – inability to fall asleep or stay asleep.

- Restless Limb Syndrome – a condition where the arms and/or legs jerk or move involuntarily during sleep, often interrupting the sleep of the affected individual or their partner.

- Jet lag – a problem that can lead to fatigue in someone who regularly crosses multiple time zones and has an irregular sleep/wake schedule.

- Narcolepsy – a condition in which a person has sudden attacks of sleepiness for no apparent reason during the day.

The direct approach

In this situation, the dentist works directly with the patient in the treatment of their sleep disorder. The sleep disorders that your dentist will treat are most often called sleep-related breathing disorders. They include2:

- Snoring – loud sounds made during sleep with inhalation, caused by the vibration of unsupported tissues in the airways.

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) – interruption of breathing during sleep that lasts 10 seconds or more. It is often associated with waking up and can result in a measurable drop in oxygen saturation.

- Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS) – a condition associated with increased airway blockage or increased airway resistance, usually without a drop in oxygen saturation.

- Hypopnea – narrowing of the airways, which leads to decreased airflow and reduced breathing effort. This can be considered a partial airway obstruction, with an associated drop in oxygen saturation.

- Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) – a frequently used term that combines the symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea and hypopnea into one single category.

Sleep breathing disorders are responsible for the vast majority of sleep disorders and are very prevalent in our society. As noted, these disorders may be associated with a reduction in the patient’s blood oxygen saturation during sleep, and snoring is also a common situation. Patients with sleep disorders also experience sleep fragmentation or frequently disrupted sleep. This pattern is associated with frequent waking, and the affected person often gets up feeling tired, as if they did not sleep during the night3.

Sleep bruxism

Another condition associated with sleep-related breathing disorders is sleep bruxism4. Traditionally, bruxism has been seen as a condition that occurs in connection with stress or another behavioural problem, or in association with occlusal problems. A recent study demonstrated that bruxism is controlled through the central nervous system and is linked to the dopaminergic system5. Bruxism occurs primarily during NREM (non-rapid eye movement) sleep, stage 2 sleep and to a lesser extent during REM (rapid eye movement) sleep, which are not the deepest stages of sleep. REM sleep is characterised by rapid eye movement during sleep with specific EEG activity, whereas in NREM sleep there is absence of eye movement at a specific level and different EEG activity.

Sleep bruxism is seen as a disorder that intrudes on sleep and occurs during sleep, but it is not the main sleep disorder. Bruxism is defined as “a stereotyped movement disorder characterised by grinding or clenching of the teeth during sleep”2.

Ohayon et al. (2001)4 found that sleep bruxism can occur in association with snoring and sleep apnea. In fact, sleep bruxism is more likely to occur with sleep-related breathing disorders than due to anxiety or stress. (Note: The study assessed the entire spectrum of bruxism and found that those at risk for having additional conditions, i.e., increased risk factors, were associated with sleep bruxism.) In that same study, it was observed that one-third of patients with sleep bruxism reported feeling tired in the morning.

Given that these conditions are commonly seen in dental offices, dentists have the knowledge and tools necessary to assist patient with sleep disorders, and can advise and apply an intraoral device that repositions the jaw to assist in opening the airway. The dentist will treat the patient with a device after consulting with the patient’s physician or sleep breathing disorder specialist. In many cases, the patient may undergo an overnight sleep study, called a polysomnography, to determine whether they have sleep apnea or OSAHS and the severity of the condition.

Many patients diagnosed with sleep apnea or OSAHS are introduced to nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) as a form of treatment. The CPAP consists of a mask that fits tightly over the nose and a small generator connected via a hose to the mask, which forces air through the nose to pneumatically open up the airway. This treatment method is very effective, but is often not well tolerated due to restrictions of movement during sleep, air leaks around the mask, and dryness of the nose and/or throat. Another problem with CPAP is that this treatment may not be effective in patients with apnea who are not sleepy6.

In addition, patients who snore but do not have apnea (and who make up a large number of people with sleep disorders) and do not find CPAP helpful, may need an alternative type of therapy. Historically, surgery has been the most commonly sought out procedure because patients are more aware of it as a treatment for snoring. Surgery, particularly soft tissue revision surgery, may have limited success and is irreversible. Today, an oral device that repositions the jaw is a well-accepted option with a high degree of success7,8.

The effects of sleep breathing disorders

Sleep-related breathing disorders have been shown to be associated with a wide variety of sequelae. Some of the effects include9:

- increased incidence of motor vehicle accidents10

- excessive daytime sleepiness

- memory loss, especially short-term

- impotence or loss of sexual desire

- hypertension and other related cardiovascular diseases

- morning headaches

- a feeling of general fatigue

The overall goal for treating sleep-related breathing disorders is to improve the individual’s quality of sleep and, therefore, improve their quality of life. Treatment and management goals include:

- improve sleep quality

- reduce daytime fatigue

- improve partner’s sleep

- reduce or eliminate headaches

- better control or management of hypertension and related health conditions

- improve memory

- improve libido

- reduce the risk of motor vehicle accidents

- improve quality of life

Certain observations made by the dentist should raise the suspicion that the patient suffers from sleep-related breathing disorders. Some of the following are considered prevalent in these patients9:

- Increased neck size.

- Advanced age. With age, the risk of sleep-related breathing disorders increases. At age 40, the prevalence of snoring is 40% in men and 20% in women, and at age 60, the prevalence is 60% in men and 40% in women.

- Weight gain. With weight gain, the potential for snoring or having OSAHS increases.

- Other family members snore or have apnea. There appears to be some genetic predisposition, but this has not been clearly defined.

- This condition is strongly related to sleep breathing disorders.

- Smoking and alcohol use. There appears to be a higher incidence of sleep breathing disorders in those who smoke or consume alcohol regularly.

- There are numerous studies that correlate hypertension with sleep breathing disorders. This seems to be related to an increase in sympathetic nervous system tone11,12.

- Enlarged tonsils and/or adenoids. The presence of these structures is often associated with sleep breathing disorders, especially in younger patients13,14.

- Gastroesophageal reflux. The presence of this condition often accompanies sleep breathing disorders because of negative esophageal pressures that are associated with negative airway pressures.

Therapy with oral devices

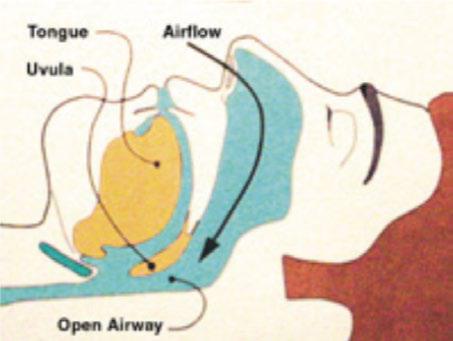

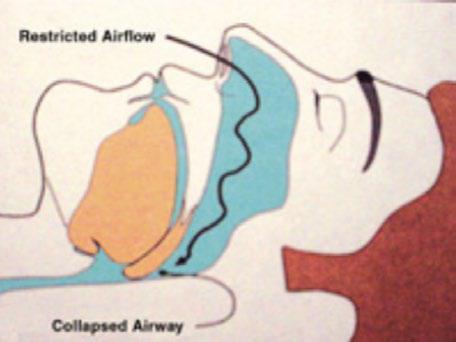

The use of oral devices that reposition the jaw during sleep are now more widely accepted by the medical profession and by physicians specialising in sleep medicine15. The purpose of the device is to keep the airways open during sleep, as illustrated in Figure 1. During sleep, the airways of a patient who snores or has sleep apnea collapse, causing an airway restriction that can lead to snoring and apnea, if sufficiently significant (Figure 2).

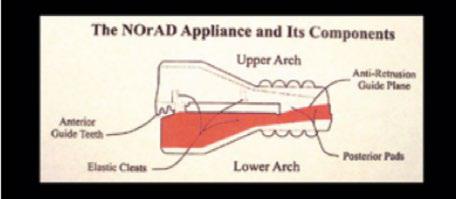

Typically, the oral devices that are used to treat sleep-related breathing disorders are composed of maxillary and mandibular components that are firmly attached to the upper and lower teeth in each arch and are held together in a way that allows jaw repositioning and the movement of the tongue away from the back of the oropharynx, preventing the mandible and tongue from returning to the airway, causing airway restriction or obstruction (Figure 3). Also, the muscles that control the airways (and the jaw) are stretched to open or dilate the airways. There are many theories as to why this type of device works so effectively. Schwab (2001)16 demonstrated that, with mandibular repositioning, the airway is opened and the greatest impact is on the lateral dimension, not on the anteroposterior dimension.

The advantages of using an oral device are that it is reversible, non-invasive, and generally convenient for the patient. It is less intrusive than CPAP and has a higher degree of success when compared to most surgical procedures17. The availability of oral devices has increased and published studies have demonstrated their effectiveness for snoring and sleep apnea. One study in particular, which analysed a very large number of patients, demonstrated the effectiveness of oral devices for snoring and sleep apnea7. Seeing as dentists are familiar with the use of intraoral devices at night, treatment of snoring with oral devices is increasingly being recommended by dentists. The ability to provide this service increases with practice and can have a positive impact on patients suffering from sleep-related breathing disorders.

Conclusion

Sleep-related breathing disorders (snoring and sleep apnea) are a common condition, and alternative and conservative approaches to their treatment are increasingly being sought out. Dentists are now part of the team of healthcare professionals who can care for these patients.